Historical Background when the Legendary Movement was born

1970 was a year of great ups and downs for the mechanical chronograph. The vaunted Omega Speedmaster helped bring the crippled Apollo 13 space capsule back to Earth. James Bond’s Rolex Cosmograph helped 007 foil Blofeld on a mountaintop lair in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. And it had been only a year since the great riddle of making a self-winding chronograph was solved, with several companies crossing the finish line in what was horology’s version of an arms race. Fresh off of this triumph, the market was awash in great chronographs, like the Zenith El Primero, the Heuer Monaco and the Breitling Chrono-matic, all still icons to this day. Sarcastically, what should have been the dawn of a decade of glory for these automatic timepieces was prematurely overshadowed by a new, even more revolutionary invention: the quartz movement.

Within a couple of years, no one cared if their chronograph was self-winding. Quartz watches were all the rage — light, durable, infinitely more accurate and growing cheaper by the year. They were the future while mechanical watches were century-old relics — heavy, complicated and expensive. In perhaps the most telling indication of the mechanical watch’s demise, even James Bond switched from his reliable Rolex to a digital Seiko for 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me.

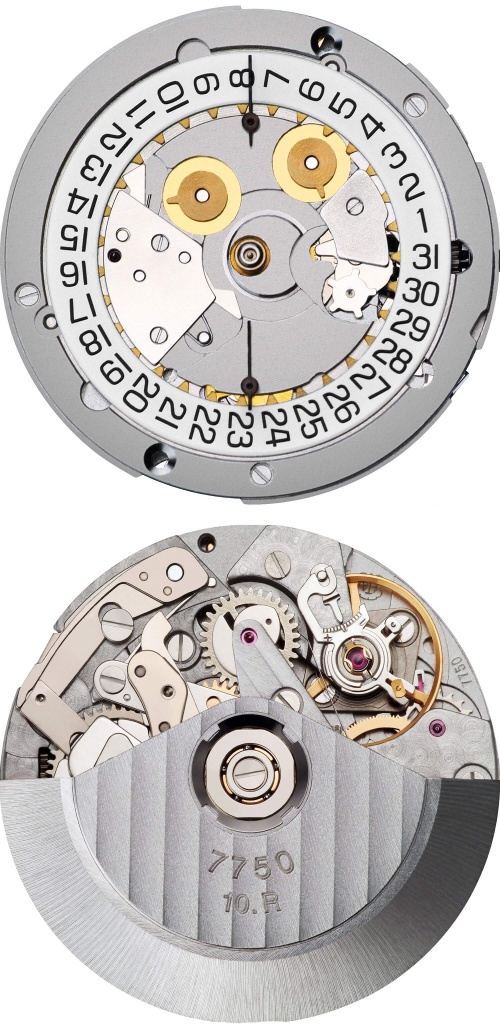

During this dark period of the early ’70s, a humble watch movement was developed that may have saved the mechanical chronograph from the dustbin of history and is still being made to this day, found in countless timepieces from humble entry-level watches to expensive perpetual calendar masterpieces. That movement is the ETA 7750 or, as it was formerly and still more commonly known, the Valjoux 7750. It is a movement that inspires heated debate among watch connoisseurs, equally revered and laughed at. Nevertheless, no one can deny the impact this movement has had on the watch industry.

Most of the chronographs of the 1960s used a delightful little mechanism called a column wheel to start, stop and reset the stopwatch functions. Renowned for its precision and snappy response, the column wheel took skill to produce and was seen as a high achievement for a watchmaker. Ironically, it didn’t lend itself well to mass production or low cost and was an easy target for the cheap hordes of quartz watches coming out of Japan. The mechanical chronograph languished.

The story of the turtle and the hare

The history of Caliber 7750 started when Valjoux found itself in somewhat of a predicament.

In 1969 Zenith-Movado introduced its first automatic chronograph movement: the El Primero. And Breitling, Hamilton, Heuer, Buren and Dubois Dépraz had joined forces and launched the Chronomatic movement in that same year.

Being left alone has put Valjoux in a tight spot, and the company decided that it was up to its fresh hire, Edmond Capt, to get the company out of it. Valjoux not only wanted him to develop the movement as quickly as possible, but it also needed to be a robust, reliable, and accurate automatic chronograph that was relatively inexpensive to make and included a quick-set day and date.

As if this wasn’t enough pressure, by this time the Japanese were already conquering valuable market positions with their quartz watches, which would later have a major impact on the history of the 7750.

To speed up the development Capt used the Valjoux Caliber 7733 as his starting point, a manual-wind chronograph. This wasn’t his only advantage because Capt also had the help of Donald Rochat and a computer to make drawings and calculations. The latter may sound like a given now, but back then it was a rarity, even in the Swiss watchmaking industry.

What made the 7750 so different was that its operating system didn’t rely on column wheels. The 7750 is a coulisse-lever escapement, meaning that the stopwatch functions are driven by levers that push an oblong cam back and forth, alternately starting, stopping and resetting the chronograph. The architecture of the 7750 lent itself to easier mass-production than did column-wheel calibres. The movement was not as refined as the Zenith or Calibre 11, but its relative crudeness is made up for by its robustness. While being an incredible innovation, by the mid-’70s quartz was king and there wasn’t the call for a high volume of mechanical chronographs and the movement remained largely dormant.

By the mid-’80s, the Swiss watch industry was showing signs of life thanks in large part to the cheap quartz Swatches that were all the rage. Many companies survived the Quartz Crisis by consolidating and sharing resources. Ébauches SA, now known as ETA, was absorbed by the Swatch Group and cranked out movements for any number of watch companies. While quartz was still on top, a renewed interest in mechanical movements led to a renaissance of automatic watches. Proud old names of watchmaking were resuscitated — Omega, IWC, Longines — and started selling old technology to a new generation. Like a twist in its destiny, it was finally time for the Valjoux 7750 to have its moment in the sun.

With the watch industry just back on its feet, in-house production of column-wheel chronographs was not practical — they required considerable design and manufacturing resources and were expensive to make and to sell. The Valjoux 7750 was the perfect answer and the movement found its way into countless mechanical chronographs from everyone from Tissot to Sinn to TAG Heuer to Omega.

Bizarre characteristics that makes the fame

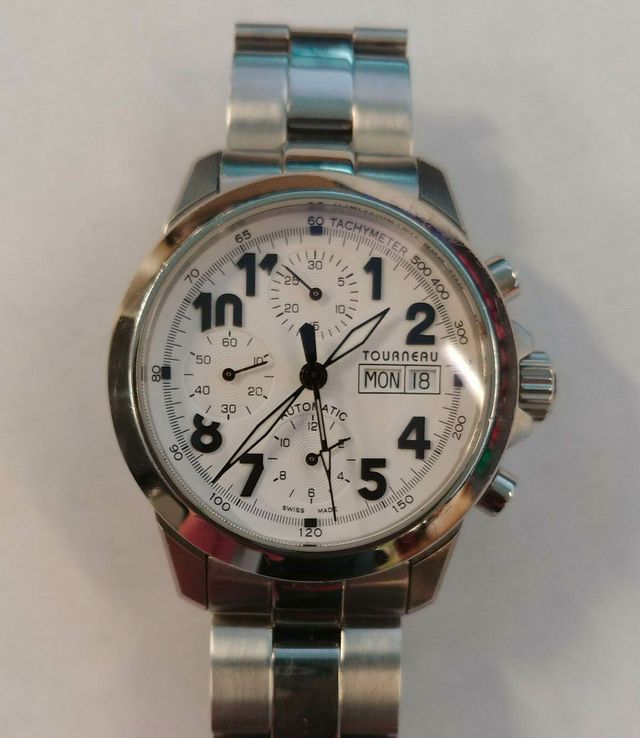

People who know watches can usually tell a Valjoux 7750-powered watch just by holding it. It is characterized by its rather stiff pusher action, sometimes by a slight backlash of the seconds hand as the chronograph engages and by the familiar “wobble” of the winding rotor when it spins inside the case. These traits annoy some and are endearing to others. The movement is not only simple and rugged but it is also highly flexible. While the most common iteration is a three sub-dial layout, the 7750 could be adapted to display a date, the day and date, two subdials (in lieu of three) and even a moonphase complication. Watch companies could order the 7750 however they chose and either drop it into their case as is, or modify it in-house.

Nowadays, walk into any watch dealer looking for a mechanical chronograph and the majority of timepieces you’ll see have a Valjoux 7750 ticking inside, no matter what the watch company has renamed it. This ubiquity has led to a sort of snobbery among watch geeks who tend to prefer in-house column-wheel movements. Regardless, it’s like the venerable Mercedes 280 Diesels that have done time as third-world taxis and limousines alike, the Valjoux 7750 cannot be dismissed as a second-rate movement. It is the motor that revived the mechanical chronograph for a new generation and has powered countless fantastic timepieces. Now, with the Swatch Group threatening to cut off supply of ETA movements to companies outside its domain, it remains to be seen what the future of the 7750, and the mechanical chronograph, holds.

Origins of the Fluted Bezel

While we think of the fluted bezel as a decorative element on today’s watches, it had its origins in the very first waterproof watches. Rolex reports that when the Rolex Oyster first appeared in 1926, the fluted bezel had a functional purpose: it served to screw the bezel into the case helping to ensure that the watch was waterproof. The fluting on the bezel was identical to the fluting on the case back, with the same tool being used to screw-down both the front bezel and the case-back. As you can see, this fascinating bezel type was built into this watch, which gives its a classy, retro look.

To help you better imagine how an automatic chronograph wristwatch works, please have a look at this video, in which I operate all the functions of this watch.

6 Popular Watches with Valjoux 7750 Movement

In 2009, Longines wanted to strengthen its position in the chronograph market with an automatic column wheel-controlled movement. Thus, the Swatch Group-owned brand took an ETA Valgranges A08.L01, which in itself was based on the 7750, and equipped it with a column wheel, vertical clutch, oscillating pinion, and a self-adjusting two-armed reset hammer to create Longines Caliber L688. That caliber is at the heart of the two beautiful black and white-tone chronograph versions below.